|

Dodge City Showdown

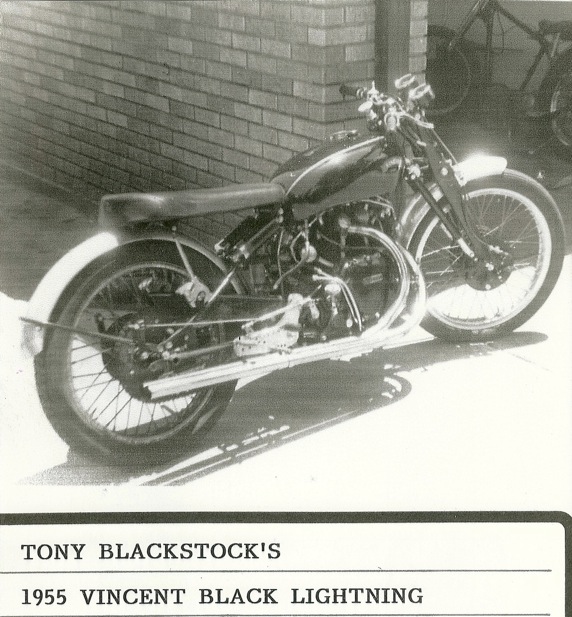

By Tony Blackstock

Introduction by Bev Bowen

Before you read Tony’s

entertaining and enlightening “Lightning” story, I figured it

would be helpful to give the reader a bit of background on Tony and his Black

Lightning and also a bit about the central scene which is the focus of the

article.

For more on the story on

Tony’s ownership of the Black Lightning, look at “MPH” issue #709. There,

commenting on what became more famously Bill Cottom’s BL, Tony let us know

the bike had a successful racing history while he owned it. This was news to

many of us, so I asked Tony if he would pen at least some of that adventure

for us, and he quickly obliged, writing the entire tale while on vacation in Montana.

As Lone Star Section

Organiser, I have a special interest in Vincent history, Texas style! While

Tony no longer lives in the state, he grew up in Abilene, a town about 3

hours west of Dallas. His Lightning was maybe the last that came from Stevenage, in 1955. It was also the only one we know of that came to Texas to its original

owner, although it was a bit convoluted how all that happened (again, see

#709).

I have recently met

numerous Texans who had a hand in Vincents in the ‘50s, and hope to get some

picture and stories, eventually, to share with the VOC. I know this will be

delightful for Lone Stars, and we’ll see if others enjoy it, too!

As for Dodge City, it’s a

town in West Kansas. Back in the 1880s it was a bustling “cow town” and home

to lots of Wild West people and stories. Even some non-USA folks will recall

the long-running TV series, “Gunsmoke,” which used Dodge City as the main

setting, with Marshall Matt Dillon opening each segment with a “showdown”

quick draw on the main street. Well, Tony had his showdown, there, too! I

think you’ll enjoy his story!

Bev Bowen

In the ‘50s Dodge City was

the Daytona of the Midwest. Each summer Dodge City hosted an AMA National,

featuring a Class “C” ½ mile (on a fairgrounds horse racing track), a Class

“C” roadrace (on a deactivated air base), and a variety of Sportsman events

including road races and drag races. I had been there once before as a

spectator and resolved to make it an annual pilgrimage from my home in Abilene, Texas.

In 1955 I had ordered and

received a last of its kind Vincent Black Lightning – a great motorcycle

which lived up to every bit of the legend it had already become. Although it

had originally been built at the factory for top speed runs, I was to use it for

¼ mile drag racing.

Drag racing was all the

rage then, and in an effort to curtail it on the streets, the City of Abilene had donated use of the old Municipal Airport to a local car club for use as a drag

strip. That summer of 1955 was the proving ground for the new Vincent which

took on all challengers and won every time.

Then in the following year,

1956, there was new development. The City arbitrarily removed part of the old

runway and put up a wire fence at the end, cutting off half of the runoff area.

The car club hosting the drags decided there was still enough room and

started off the new year holding weekend events, as usual. I surveyed this

new, shorter strip and the ominous fence with some trepidation; but, valor

being the better part of discretion, I entered the first race, anyway.

I cannot recall who I was

pitted against, but I can recall that first run vividly! I got off the line

too slowly, but soon passed my competitor. The finish line quickly

materialized, and I shut off the throttle and hit the brakes. Still, I was

almost immediately upon the new fence. In those pre-disc days the dual brakes

on the Vincent were among the best available, but would this be enough?

The bike hit the fence with

a sound somewhere between a “thud” and a “twang,” very nearly throwing me

over the handlebars. But, I was OK! The brakes had done their job admirably;

however, that was to be my last run, locally. The short runoff was sufficient

to accommodate most of the competition, but nowhere near long enough to allow

for the triple digit speed of the Vincent. Future runs would be at other

(longer) strips around Texas (and at Dodge City).

During 1956, between races,

I had become good friends with Larry Beall. Larry was an expert rider and had

considerable experience in all types of motorcycle racing. Larry had ridden

the Vincent a couple of times and was much impressed with its power and

speed. It was he who first suggested that I take the Lightning to the

Nationals at Dodge City and try to win the top fuel class. Up to that point I

had only run the Lightning on pump gas; however, Larry had experience in

running alcohol and nitro-methane and offered to help set up the bike to run

fuel. I agreed to go ahead with this plan. It was, after all, time to step up

to stiffer competition as the Vincent had easily beaten everything so far

encountered. Dodge City was sure to draw the best of the best from all over

the Midwest.

After burning the midnight

oil with Larry a few times, it was decided we would make this a team effort.

Larry and I would both go to Dodge City and race the bike in the open fuel

class. Larry’s Dad, Sam Beall, at first voiced some objections to our going,

but when he realized we were determined he did a 180 degree turnabout and

volunteered to join the team. Sam was the local Triumph dealer, was also an

excellent mechanic, and had always served as Larry’s pit crew in past races.

We were glad to have him. Besides, he also offered to help with travel

expense – which was even better!

We started by prepping the bike

and making sure everything was in top condition. We altered the ignition

timing several degrees. The main jets were drilled out to the maximum

possible and both needles were reset to their highest position. The tank was

filled with straight methanol and I made several satisfactory test runs. Due

mainly to the expense of the nitro-methane, we decided to wait to add any

nitro until we made further test runs at Dodge City.

The team responsibilities

were split-up as follows: Sam was crew chief and head mechanic with my

sharing any wrenching required. Larry was responsible for blending the fuel:

methanol, several blending agents and a yet to be determined percentage of

nitro-methane. After much discussion and soul searching on my part, we

decided Larry – instead of me – would be the rider. I, of course, had done

all the racing of the Vincent up until then and knew all the tricks to make

it run best. Larry, on the other hand, had more overall racing experience

than I. But the final deciding factor was size/weight. I was 6’2” and weighed

in at 200 lbs. Larry, although stoutly built, was diminutive in size and

weighed in around 120 lbs. Larry and I decided the best plan would to show

him the proper way to ride the bike. (Note: the Vincent Black Lightning did have

its own peculiarities and demanded a certain Vincent-unique method of riding

to make it perform properly. This will be explained later). At the last

minute Larry’s kid brother, Freddy, asked to go along and volunteered his

motorcycle to be used as a chase bike, which was very helpful.

We loaded the Black

Lightning and the chase bike onto a two-railed motorcycle trailer, which was

hooked to my Ford Fairlane. The fuel was poured into one gallon vinegar jugs

and set into a large wooden box to keep them from turning over, loaded into

the trunk along with Sam’s toolbox. We had no spare parts. Bank credit cards

had not yet been introduced in 1956, and we had just enough cash to get us to

Dodge City and back. By today’s standards we were a woefully ill-prepared,

rag-tag crew. But we were a fairly typical lot in the 1950’s.

We drove straight through

to Dodge City arriving 3 days early to make some practice runs, familiarize

Larry with the Vincent riding technique, try different nitro-alcohol blends

and (time permitting) watch the flat-track races.

Upon arrival we checked

into the cheapest motel we could find and went straight to the old airfield.

We started our practice runs by mixing up a mild fuel blend of 90% methanol

with 10% nitro. It was my first experience with running nitro, and I was

amazed at the results. The Vincent had always been bullet-fast, but now it

had become a rocket ship! Further, the more nitro we added the faster it

went. We ended up with a mix of about 70% methanol and 30% nitro.

Then we encountered

problems. The first problem we had was the seat. As equipped from the factory

the Black Lightning had a flat seat somewhat resembling an ironing board …

presumably to accommodate a “Rollie Free” style prone position. With the

increased acceleration we now had, it quickly became obvious that this was

not the right seat for our purposes. On gasoline the bike had always pulled

hard, but I had compensated for this by pushing hard forward on the

rear-mounted footpegs. Now the bike was pulling so hard that it would try to

accelerate right out from under you! What was needed was a seat with a

butt-stop in back, which we didn’t have.

The second problem was the

tachometer. We had no sooner arrived than for some inexplicable reason the

tach cable parted. We chalked it up to bad luck, removed the cable and went

ahead without it. We felt that we could do well enough to win by shifting by

ear.

A word about parts

availability here. In the 1950’s motorcycle shops were few and far between,

and in small to medium sized cities (like Dodge City) a bike shop was usually

more of a gathering place for local riders than anything else. A typical

small town bike shop might have 2 or 3 motorcycles on the showroom floor. The

owner was probably the only employee, serving as salesman, mechanic, partsman

and everything else. His stock of parts would largely consist of motor oil,

spark plugs, master links, handlebar grips and not much else. Virtually all

parts had to be ordered. We all knew this and made no effort to find a local

source for a new tach cable or different seat.

The only other problem we

had was that the tires seemed to be losing some air; but when we pumped them

up and checked the tire pressure the next morning, they were both holding

pressure.

The second day we also

spent practicing at the airstrip. We started out by familiarizing Larry with

the methods I had developed to get the best performance out of the Black

Lightning.

First was shifting. It was

impossible to shift a Vincent without letting up on the throttle at least

momentarily. Shifting at full throttle would inevitably result in the bike

jumping out of gear and potentially even result in a damaged transmission. If

I recall correctly, this was called out quite clearly in the Vincent Owner’s

Manual. However ... with practice proper gear shifts can be done more

quickly than one might think …. ‘chop throttle – engage clutch – shift –

release clutch – open throttle’ … all can be done in the blink of an eye

without the loss of momentum.

Second was dealing with

clutch slippage. The Black Lightning was not equipped with a conventional

multiple disc clutch. Clutch slippage with conventional clutches could be a

problem when dealing with gobs of horsepower at high speed where wind

resistance can put a strain on the best of clutches. I was told that the

Vincent centrifugal clutch was developed by the factory to deal with this. It

was designed so that as speed and rpm increased, the centrifugal shoes would

expand harder and harder against the outer drum eliminating clutch slippage

at higher speeds.

To deal with low speed

clutch slippage (before the centrifugal shoes had enough inertia to lock up),

the factory added an outer single disc as a starter plate – just to get the

bike going. Bearing in mind that this clutch was primarily designed for top

end runs, the whole arrangement did its job quite satisfactorily.

In drag racing far more

stress is put on the clutch at low speeds off the start line instead of high

speeds. To compensate for the single disc being overstressed and slipping at

the start, we did two things: First, in between runs we would dismantle the

outer clutch and liberally coat the single disc with Copsiloy (the anti-slip

paste). Second, and very unconventionally, at the start I advised Larry to

stand up straddling the bike without putting any weight on the seat

whatsoever, rev the engine to about 2000 rpm and, at the drop of the flag

dump the clutch which would start the rear tire spinning, open the throttle

and then sit down. The result was the rear tire would continue

to spin (instead of the clutch slipping) and the Vincent would be off. Weird,

but it worked … and in racing that’s all that counts. Third, and the last bit

of Vincent-eze I gave Larry was to not over-rev. The black Lightning was

built for torque, and (I suspect due to the camshaft grind) would peak out

rather quickly. To be sure, it certainly had an enormous amount of power;

however, when it peaked out, you immediately sensed it and knew it was time

to shift or else the motor would flatten out and ground would be lost.

Larry was a very talented

rider and a fast learner. He quickly mastered all that I had passed on and in

short order he was equally proficient as I in Vincent-eze. With his 80 lb.

weight advantage I felt we had a good chance of winning.

The second day of practice

went very well until the end of the day. After many short runs Larry decided

to make one last, longer run. The airfield runway had been for large aircraft

and had plenty of room. Larry started off well, ran the bike through the

gears and disappeared in the distance. A minute later I took the chase bike

and rode down to retrieve Larry and the Lightning. He had indeed gone a long

way and was at the very end of the asphalt. When I arrived, I immediately

knew something was terribly wrong. Larry was sitting on the bike, white as a

sheet and shaking like a leaf. Both tires were flat and there were giant

weaving black streaks at the end of the asphalt leading to the bike.

Larry was barely able to

speak, but after a few minutes he regained his composure and explained what

had happened. At the end of his overly long run the bike started to feel

funny. When he tried to shut down, the bike shook violently. In an effort to

regain control, he re-opened the throttle and the bike straightened out. He

again tried to slow down and the same thing happened again. At this point the

end of the runway was coming into view. There was no option except to someway

stop the bike before running out of asphalt. He eased off the throttle and

tried to apply the brakes. The bike slewed sideways to the left, very nearly

going down. At the last second the bike righted itself and slewed sideways to

the right, again almost going down before repeating the same scenario several

more times. Larry had taken quite a beating. His legs were off the pegs and

flailing against the bike each time. This whole nightmare was, however,

scrubbing off speed; and through an Herculean effort and his exceptional

riding ability Larry somehow stayed on the bike and eventually brought it to

a stop.

After tending to Larry’s

bruised and bleeding legs, we all tried to figure out what went wrong. Both

tires were completely flat, so Sam dismantled the tires to find out why. To

our surprise the tires appeared to be OK and the tubes were both holding air!

There were no nails or anything else to be found which would explain the loss

of air. Sam reassembled the tires and put them back on the bike. Sam and I

took the Black Lightning back to the airfield, leaving Larry at the motel.

With a lot of trepidation I pushed the bike off. As usual it started right

away and I carefully rode it down the airstrip. Nothing happened! The Vincent

was running straight and true. I ran it through the gears several times

without incident. I did not, however, push my luck to test its top speed as

Larry had. We loaded up the bike and returned to the motel. The cause of the

problem was a complete mystery. We all agreed that unless a positive solution

to our problem was found, we would withdraw from the race and not risk a

repeat of Larry’s near catastrophe.

As events turned out, by

the next morning we had solved the mystery! Up until then we had assumed that

the bike had some unknown flaw which had caused the shaking and sliding, and

in so doing had flattened the tires. In truth, the exact opposite had

happened. The tires had gone flat first which caused the bike –

at speed – to go out of control.

The solution was simple …

install valve caps! There were no valve caps on either the front or rear

tires since none of us had considered them necessary. Someone (whose identity

has been lost in time) the night before suggested that at a high enough speed

the spring loaded valve cores could be depressed by the centrifugal force of

the fast turning wheels. This explanation fit to a T what had transpired with

us. The many previous races I had run were all slower on gasoline – no such

problem had developed. Also I had, at that point, never previously run the

Vincent to its top speed. The increased speeds it was now running with the

alcohol/nitro mix had caused the faster spinning wheels to exceed the

threshold required to simultaneously depress the valve cores, expel the air

and quickly flatten both tires. This had caused the slewing and shaking that

was experienced. With the addition of two new valve caps and a couple of

uneventful test runs, we were back in business.

As it relates to the race,

it should be noted here that many of the rules, regulations and safety

standards for motorcycle racing we routinely practice today were, in the

1950’s, absent or ignored. In general such things as a barrier between the

race track and spectators, on-site ambulances, tech inspections, etc., were

not present or practiced. Specific to what next

transpired for us at Dodge City, safe distances between drag race competitors

were not required as they are today. In fact, the closer together the racers

were the better. This aided the spectators and judges to more easily see who

was ahead (and undoubtedly added to an element of excitement).

The day of the race, which

dawned clear and windless, would feature both the drag races and roadraces.

The drag races would be in the morning; the roadraces in the afternoon. Due

to the heavy schedule the races started early. First, the Sportsman classes;

finally, just before noon (ed.: High Noon in Dodge City!), the Open

Fuel Class.

The first programs went off

quickly, and before we knew it, we were up. There were to be two elimination

runs – each leading to the final top eliminator run between the two

finalists. The bikes we would be facing were all a definite step up from

anything I had previously competed against … so the Vincent would have to

perform at its very best in order to win.

From the outset it became

clear that the two fastest bikes were my Vincent and a Triumph dragster

ridden by Joe Minonno of the Dallas/Ft. Worth area. Joe was a veteran drag

racer and a consistent winner. He would be a fierce competitor. The

eliminations proceeded more or less as expected. The Vincent won its first

two rounds, likewise for Joe’s Triumph. The top eliminator would be between

Joe and Larry.

We were allowed just enough

time before the top eliminator race to dope the outer clutch plate and add

fuel. We pushed the Vincent off and Larry headed for the start line where Joe

was already waiting. The two competitors lined up side by side (and as

mentioned before, with only a foot or two separating them). Joe’s Triumph was

running 1.3/4” pipes with two enormous megaphones and was deafeningly loud.

The Vincent, on the other hand, was running the factory equipped long,

straight 1.5/8” pipes and was (comparatively) quiet.

The flagman was ready, and

after the affirmative nod from both Joe and Larry, the flag was dropped. Both

bikes got off with a perfect start. The entire ¼ mile was a neck-to-neck race

with neither bike gaining more than a foot or two on the other. Larry would

pull ahead, then Joe, then Larry. I did not know it at the time, but Larry

was having trouble. Without the aid of the tachometer (due to its broken

cable mentioned earlier) and with the fierce exhaust note of the Triumph at

such close proximity completely drowning out the sound of the Vincent, Larry

was having trouble shifting on time. The only indicator he could sense to

time his gear shifts was Joe! Larry was out-accelerating Joe and with each

gear shift the Vincent would surge ahead. When Joe caught up and edged ahead,

Larry would know he had waited too long to shift. With each shift Larry

surged ahead and then the scenario would repeat itself, continuing all the

way to the finish. The finish was almost too close to call, but when the

judges came down with the decision Joe was declared the winner and top

eliminator. Larry later agreed that indeed Joe was slightly ahead at the

finish.

Joe had run a perfect race and

won. He and his bike deserved all the credit they received for their hard-won

victory. Larry had been hampered in his effort by the lack of a functioning

tachometer, but very nearly won despite this handicap.

The drag races were over,

but we decided to stay and watch the roadraces. While the rest of the team

watched, I drained the rest of the fuel from the tank, dismantled the two TT

carbs and cleaned them to remove any residual alcohol/nitro mix, and finally

drained the motor oil to remove any fuel which might have blown into the

lower end.

On our way home we were all

a bit disheartened to say the least to come away empty-handed, especially

having come so close to winning. Once home I rejetted and retimed the Black

Lightning back to its original settings for pump gas. Although I continued

racing the Vincent on gasoline and it resumed its winning streak, I never

raced it on fuel again.

In retrospect after these

many years I realize what an astonishing performance the Vincent had turned

in. We, the ill-prepared, had taken a box stock Vincent Black Lightning and

very nearly won top honors at a National. There were no special modifications

made to the Black Lightning other than gearing and switching from gas to

fuel. I feel that it was a great tribute to the Vincent marque to have

produced a motorcycle capable of such performance. In truth it would be

decades before its speed and power would be matched and even today modified

Vincents are used successfully in various competitive events.

Tony Blackstock

July, 2009

|